That's what South Deltans are asking as they see their family docs retire, leaving many longtime patients scrambling to find a GP. Problem is, there just aren't many new doctors out there, especially those accepting new patients.

Tsawwassen resident Ingrid Abbott is one of those people now on the hunt for a new family physician after her doctors, the husband-and-wife team of Dominic and

Veronica Eustace, announced they're retiring in May. The couple operates a practice that also has a walk-in clinic component, and their departure is a story that will be repeated all over the province as older physicians hang up their stethoscopes. Noting Tsawwassen will be left without a walk-in clinic, forcing those without a primary doctor to go to Ladner, Abbott said seniors, especially, are concerned.

"In Ladner, that (walk-in clinic) will be even more stressed with the closing of this practice, but where else can all these people go?" asked Abbott. "Apparently the days of somebody buying your practice or taking it over are gone in family medicine."

Dr. Alan Ruddiman, president-elect of Doctors of B.C, formerly the B.C. Medical Association, said the shortage isn't so much about new doctors being hired away by other provinces, but is a more complex issue that has a variety of factors. It's all creating pressures that he said will become more intense as an estimated 25 per cent of doctors in the province say they plan to retire in the next five to 10 years.

"For a number of reasons we've arrived at a place, I think not just in British Columbia but nationally and internationally now, where there is a real, and not just a perceived, shortage of very skilled family physicians who come with enhanced skills and are willing to literally provide full service in their practice," he said.

"There's a generational issue where physicians that have been practicing 20, 30, 40 years, the model was when you finish medical school, you did your residency, and you came out with your residency as a family doctor. What you would do is seek a community, start your own family practice or join a practice. Traditionally, there was a buy-in into a practice. There's so many practices now where physicians are wanting to retire or delaying retiring until someone comes in."

Ruddiman noted new doctors are choosing to delay having their own practices, electing instead to work in such roles as fill-ins. It's a way new graduates prefer to ease their way into family medicine, he explained. He added for whatever reason, there's a sense among new graduates that they're not fully prepared to take on the responsibilities of a family practice.

"So if you're a solo practitioner that's planning on retiring, I would suggest they will have a lot of difficulty finding a family physician to replace them. These younger doctors, they want to work in group practice. They want to have more senior physicians in the practice that can act as a bit of a mentor and resources to them.

"They're also being trained in university to consider working in collaborative teams, so not just groups of family doctors working together but doctors who work alongside nurses and nurse practitioners and possibly care aides and physiotherapists. There is this flavour that the new generation of family physicians are choosing to practice medicine a little bit differently than their more senior or closer to retiring doctors."

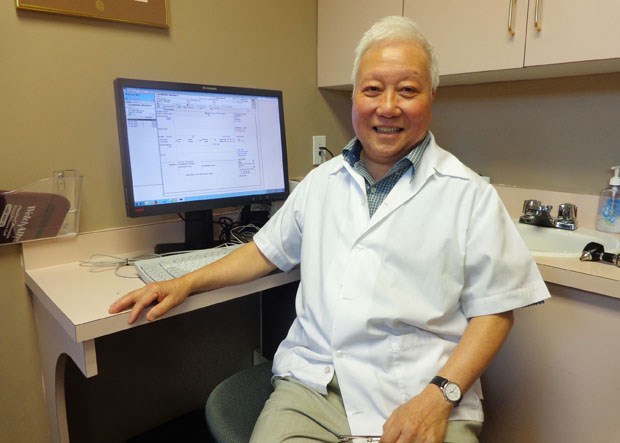

When Dr. Ken Lai retired last year after 43 years in practice in Ladner, he was replaced by Dr. Sandy Chuang, but that type of succession seems more of a rarity these days.

Ruddiman noted a big problem that's also catching up to communities is that not enough medical graduates are produced on an annual basis to support and replace the doctors who are emigrating to other jurisdictions or retiring, thus Canada has relied heavily on international medical graduates, particularly for rural communities.

UBC has tried to address the issue over the past few years by spreading out its teaching programs throughout the province, but more is needed.

"What we're looking to have is people who come out with very broad generalists skills. We certainly need specialists and subspecialists across the province, but they're not providing the longitudinal care to communities and the public," he said. "Where we need to be investing as a province is the universities and educational programs for solid generalist medicine."

Ruddiman said one survey found about 100,000 people in Vancouver don't have a family doctor, although about one-third of them were not actively seeking one.

Many people are now using walk-in clinics, not only out of necessity but also convenience, a trend that's tying up doctors in those types of practices.

Last year provincial Health Minister Terry Lake admitted he's unsure if the province would be able to deliver on its promise of ensuring every British Columbian has access to a family physician, although he noted there has been progress on that front.

Delta South MLA Vicki Huntington doesn't see it that way, saying that when the government made its ambitious promise in 2010, an estimated 176,000 British Columbians were looking for a family physician, yet last year the minister of health said that number had climbed to nearly 210,000.

"The GP shortage presents a real challenge for people in South Delta. According to the Ministry of Health, there may be over 2,000 people looking for a family doctor in our community. For the moment, they are out of luck. Each GP's practice serves 1,000 to 2,000 patients, so unless new family doctors replace those that retire, more people in South Delta will be looking for help," Huntington said.

In 2013, the government spent $132 million on a program called GP For Me, involving Doctors of B.C., formerly the B.C. Medical Association. The initiative has been able to match over 55,000 patients to primary care providers.

Delta has been involved with that initiative through a group of local physicians that's part of the Delta Division of Family Practice. The group late last year launched a website called FETCH (For Everything That's Community Health) that helps the public and health care providers access information about community health services in South Delta.

The site (delta.fetchbc.ca), created with the assistance of local health care professionals, service agencies and community partners, including the Corporation of Delta, recently saw a new feature launched linking patients looking for a doctor with available family physicians.

In a presentation to Delta council in December, Dr. Craig Martin, vice-chair of the Delta Division of Family Practice, said the goal is to help unattached patients find family doctors. Patients on the list would be contacted directly by the physicians, however Martin and other representatives of the Delta Division of Family Practice were quick to point out they didn't want to raise expectations too high because it could take months to get a response.

"Fifty per cent of us are going to retire in the next seven to eight years," warned Martin, who said that isn't good news given quite a few of the older Delta physicians have a large number of patients.

He noted UBC does not have enough new medical students entering school to fill the void, so recruitment has to take place from other provinces and countries.

"The public should be in an uproar about this because we're scrambling to get doctors from all around the world and we're fighting within Canada to get doctors over here, but Ontario is doing the same, Nova Scotia is doing the same. So we're going after the same pool of physicians. We're just not graduating enough every year," he said.

Martin added both the provincial and federal governments have a role to play.

The Delta Division of Family Practice has been working on recruitment, successfully recruiting three new doctors in recent months, but is also trying to convince some of the older doctors to stick around a little longer.

In a letter last month to Mayor Lois Jackson, who had written to government requesting an increase in the number of post-graduate medical seats at UBC, Lake responded that the province has increased the number of spaces, primarily in family medicine, which he called the area of greatest need.

Lake noted without the expansion, UBC would have graduated 672 family physicians between 2001 and 2014, however, it's been able to graduate 1,182 over that time.

Meanwhile, when it comes to retiring doctors moving their patients' files to a private storage company, Huntington said if the government can't resolve the current GP shortage, then at a minimum it should cover the document-transfer fees of patients who lose their family doctor and have nowhere else to turn.