With B.C. likely to need as many as 412 million face masks in the next 12 months, researchers at UBC are now hard at work to find a local solution - and the answer may simply be the trees.

That’s where, officials from the school’s BioProducts Institute said, fibres from pine, spruce, cedar and other softwoods can be found. These fibres have the potential to be moulded and developed into filtering materials that have a wide variety of uses - including as masks and filters in a biodegradable N95 device that can be made 100% within B.C.

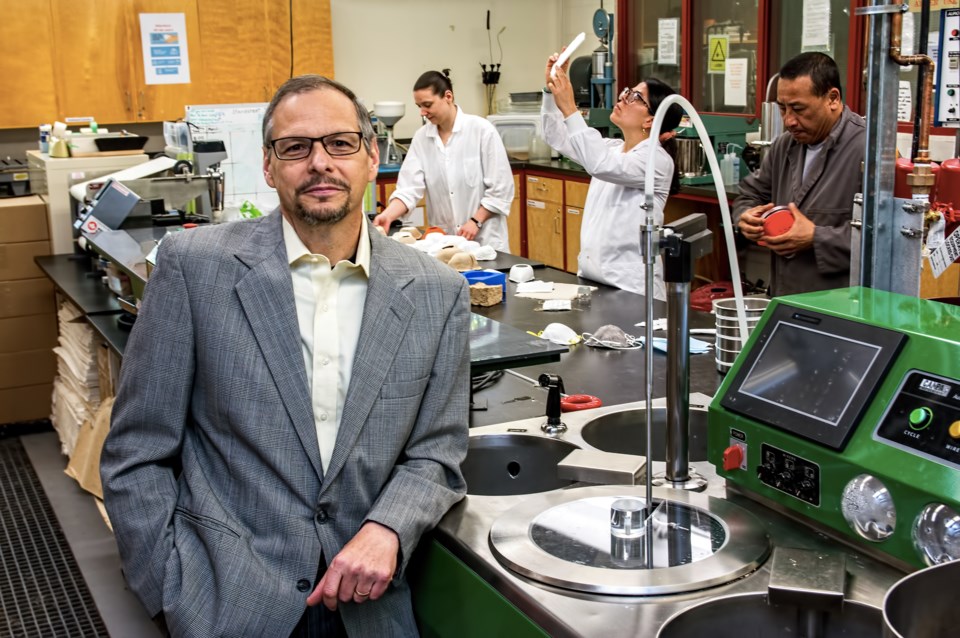

“The idea has been around for a long time - but in a different context,” said Orlando Rojas, scientific director with the BioProducts Institute. “Historically, at the UBC Pulp and Paper Centre where I’m the director, the topic of air filtration has been in research. So when we saw this issue of N95 masks, when you look at the end-of-life used masks discarded all over the place, and we immediately thought that would be an opportunity to use biodegradable material.”

After months of research, mock-ups and tests, the UBC team has now produced the first prototypes of what they call “Can-Masks,” which - if entered into commercial production in the future - would solve problems on multiple fronts because it would use local materials, be easy/inexpensive to make, and carry an added bonus of being environmentally friendly.

The prototypes are now being tested to make sure they are up to health-sector requirements, and a certification process from Health Canada is about to get underway, Rojas said. The research has so far been done completely on the school’s internal funding, but in order for the technology to be scaled up for commercial production, another model is obviously needed.

The key, regardless of which business model the institute takes, will be making sure there are the necessary machinery to make large batches of the product once scale-up for commercial sale is needed.

“A lot of things are still up in the air,” Rojas noted. “We are discussing the best way to proceed within the university. But there are a lot of investors who are already interested because this is an attractive proposal from the point-of-view of profitability and environmental impact.”

He added that the development of Can-Mask can also be a turning point for B.C.’s struggling wood-products sector, which has been looking at years of struggles as saw mills and pulp plants in the province dwindle in numbers. The demand for N95 face masks as the economy reopens without a COVID-19 vaccine - along with the fact that the Can-Masks will be a value-added product that generates more revenue and jobs than conventional pulp and paper products - means the potential for new business gains in B.C. is substantial.

“Locality was a critical part of what makes this work,” Rojas said. “Job creation is an important part of the equation we had in mind; people in the industry need to know that wood fibre can be used for more than just paper production… and that’s critical for the forestry sector, because the industry can’t continue in its current form. We have to look at new, value-added uses.”