Ten per cent of people who tested for radon in the past decade have found the radioactive gas in their homes, according to a new survey from Statistics Canada.

The 2021 poll surveyed 38,000 households across the country, asking whether they had ever heard of the colourless, odourless and tasteless gas.

Only 56 per cent said they knew of radon, and of those, 69 per cent were able to identify the gas from a list of possibilities.

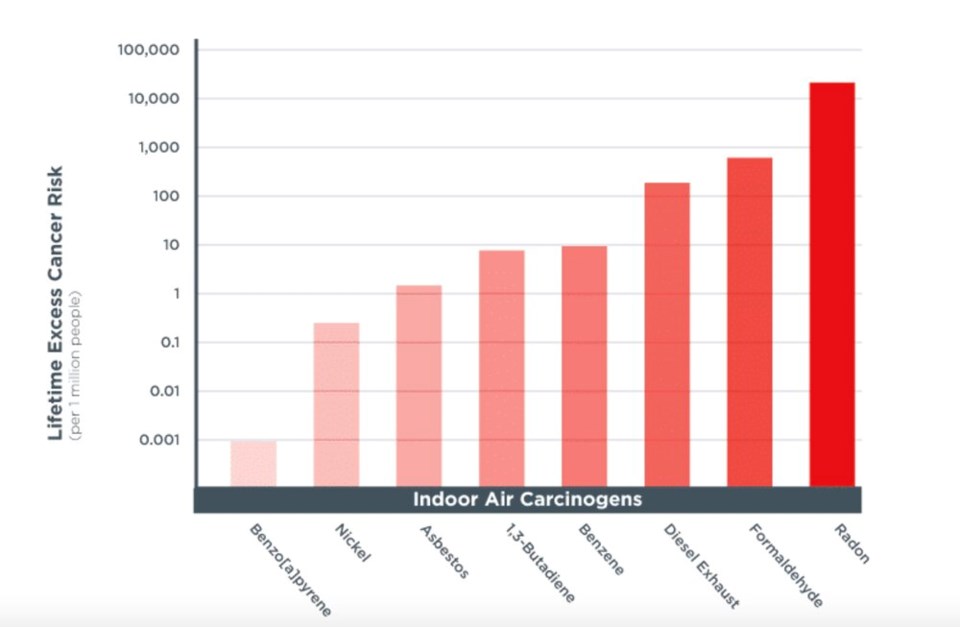

“It never ceases to amaze me how many people haven't heard about it — and it's the second leading cause of lung cancer, and the first if you don't smoke,” said Anne-Marie Nicol in an interview with Glacier Media six months after the pandemic began.

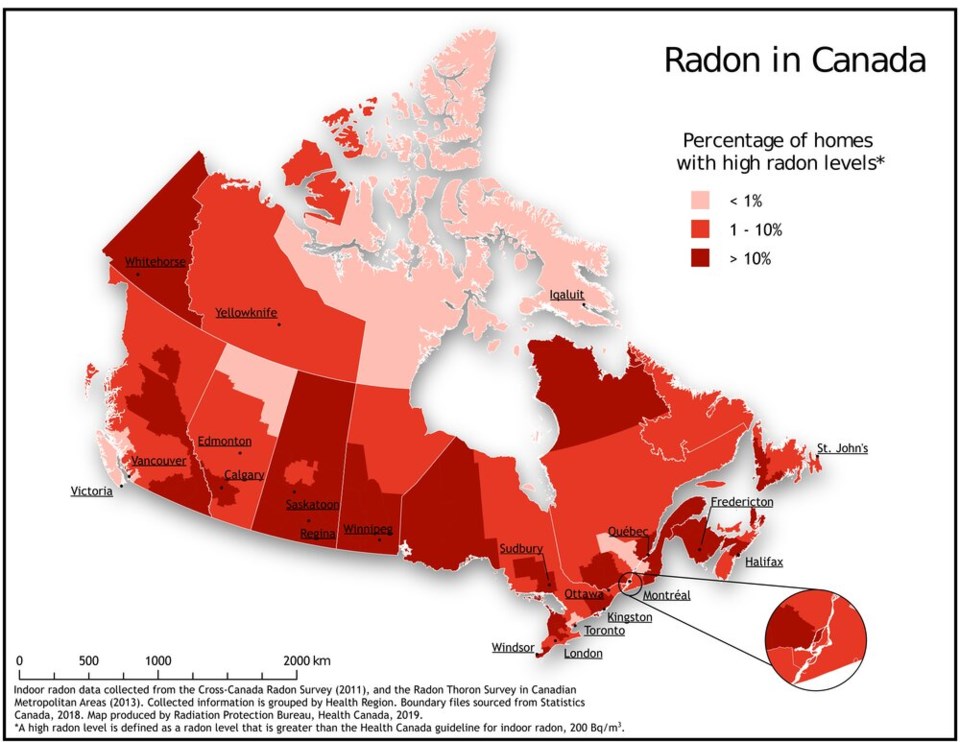

Radon surveys carried out roughly a decade ago show that in B.C., the percentage of homes with high radon levels ranges from nearly 30 per cent in the Kootenay-Boundary region to under one per cent on Vancouver Island.

Across Canada, southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba stand out with over 40 per cent of homes reporting high levels of the dangerous gas.

Health Canada estimates radon gas kills roughly 3,200 Canadians a year, more than any other environmental carcinogen after UV radiation, according to one Ontario study.

The naturally occurring gas is a product of decaying uranium in the bedrock and soil. Halfway through its lifecycle, the radioactive metal transforms into a gas, which can seep through the cracks, gaps and fissures in a building’s foundations.

Once trapped inside, it’s inhaled into the lungs where the radioactive gas bombards your cells, triggering tumour genesis — the spark that starts the development of cancer.

But predicting where high levels of radon gas are found is a challenge and can vary from province to province, neighbourhood to neighbourhood and even house to house.

Test often and test widely

Testing for the gas is the only way to know just how widespread a problem it is.

While individuals can purchase a radon test for about $50, there is a growing movement to test a cross-section of a community all at once.

Every year, the 100 Test Kit Radon Challenge calls on towns and cities across Canada to add data points to often outdated maps showing the prevalence of the naturally occurring gas.

Between 2021 and 2022, 35 communities took part, including a number across B.C.’s southern Interior.

“Health Canada has been banging this drum of getting people to test for a while, but this kind of targeted community-level testing to catch what radon is doing is really getting the ball rolling, getting people engaged and involved,” Nicol said.

In some communities, testing led to some startling numbers.

In Clearwater and Lake Country, more than half of homes tested above Health Canada’s guideline of 200 Becquerels per cubic metre — the unit scientists use to measure radioactivity.

Elsewhere this past year, the percentage of tested homes above Health Canada’a radon limit hit 48 per cent in Grand Forks; 46 per cent in Revelstoke; 41 per cent in Peachland; 38 per cent in West Kelowna and 22 per cent in Kelowna.

This fall, the testing program is also coming to Kimberley, Keremeos, Salt Spring Island, Chilliwack and Mission, according to the group’s website.

The problem has been recognized as a sufficient threat to public health that the BC Centre for Disease Control has attempted to map radon's prevalence.

It’s not just people’s private dwellings that are at risk. Radon has been found in public buildings, hospitals and schools.

In recent years, Nicol helped schools across the Sea to Sky corridor test for the gas, leading several to take action to mitigate radon levels. But as of 2017, only eight per cent of B.C. schools had tested for radon, a number dwarfed by 100 per cent testing rates in schools across the Yukon, Saskatchewan and the Maritimes.

There are no regulations to test child-care facilities, which are often in basements and therefore at higher risks, says Nicol, who has been working to get the word out.

Radon levels can vary by property

No matter what part of the country, the varied geology of a region or neighbourhood means concentrations of radon gas could remain low in one block and ramp up down the road.

Some maps indicate geologic conditions give Vancouver’s North Shore a higher relative radon hazard compared to the rest of the Metro Vancouver region. But on the ground and from one house to the next, a spectrum of radon readings can occur no matter what city you are in.

Unlike asbestos, radon is not limited to older homes. In fact, newer, weather-sealed homes may be more energy-efficient, but they can also seal gas in, exacerbating exposure.

In one home, radon levels can fluctuate throughout the day as residents open a door, or turn on the oven or heat, said Nicol.

That’s because radon gas — like all gas — tends to move away from cold spaces and towards warm ones. As people heat their homes in the winter, warm air rises, creating pockets of low pressure near the ground. In what’s known as a “stack effect,” the gas rushes from the ground to fill the space, passing through cracks and gaps in the foundation, sump pumps, fittings or windows.

“Every house is different and you're not going to know until you test,” said Nicol.