Picture yourself driving from Downtown Vancouver to Ladner, or perhaps out to Langley or Cloverdale, seeing nothing but an endless sea of single-family subdivisions and warehousing, one community pretty well looking the same as the next.

It’s a scenario that could very well have played out in the Lower Mainland had the New Democrat provincial government in 1973 not introduced the Agricultural Land Reserve, a unique experiment that saw large tracts of farmland in B.C. frozen from any future development.

Highly controversial at the time, several decades later it’s widely viewed as a critical piece of legislation which protected the province’s ability to grow its own food, especially in the Lower Mainland, which has seen substantial population growth, but also happens to possess some of the best soil for growing crops in the country.

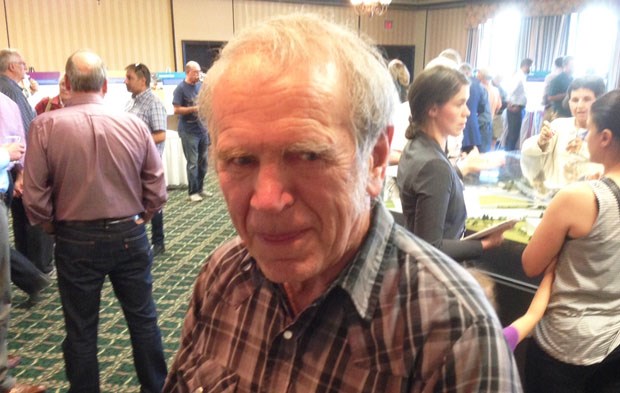

“It did something more than just save farmland. It contained Vancouver and encouraged a fair amount of community planning and not allowing sprawl everywhere,” says Richmond city councillor Harold Steves, one of the architects of the ALR and former NDP MLA back in the early 1970s.

Steves says prior to the ALR, local city councils mostly dealt with land use decisions when it came to farmland, something that would have led, thanks to politics, to a gradual erosion because the reserve has always been under constant pressure.

“Richmond, for sure, wouldn’t have any farmland and most of Delta as well. The ALR is still under threat but a lot more people now know how important it is and want to preserve it, largely because we’ve got quite a food movement now where people are saying we need locally grown food, not depending on it coming from California,” adds Steves.

More than 17,500 farms in B.C. currently operate in the ALR, employing in excess of 44,500 workers and producing more than 200 different agricultural products. The total farm capital in B.C. in 2016 was more than $37.5 billion.

Since its inception in 1973, the Agricultural Land Commission, which oversees the reserve, has considered more than 45,000 land use applications, including subdivisions and exclusions.

First elected in 1972, long-time Delta council member Lois Jackson recalls there were a lot of divisive opinions in Delta when the land freeze was introduced, but now most agree farming in the Lower Mainland would be non-existent without it, while much of the Fraser Valley would look much different today as well.

“It was strange time of upheaval and we knew many of the farmers would eventually sell out or divide them into smaller parcels as they aged. There were a couple of questionable inclusions at the time like areas of the (Burns) bog and there’s just no way you could farm there. Other than that, some of us tried to look into a crystal ball at what it would look like in the years ahead if we didn’t take the position we did, and, from my position, Ladner and Tsawwassen would be just chock-a-block full of housing and shopping centres, like we’ve seen happen in Burnaby, Richmond and Coquitlam,” says Jackson.

Already upset when the government introduced the land freeze, local farmers took exception to what Harry Lash, director of planning for the Greater Vancouver Regional District, had to say in a presentation to the Delta Chamber of Commerce in 1973. He explained the land commission's philosophy was that it wasn't important farmland wasn't actively being farmed at that time.

“The land commission has said that even though farming may not be profitable now, they think it will become viable in the future with the growing food shortage,” Lash stated.

In a presentation to government that year, Delta Farmers’ Institute representative Mike Guichon, a member of a pioneer Delta family still farming today, described Delta as being “a victim of circumstance” and suggested “some of these lands are destined for other uses. Some industrial, some residential, some open space and some agricultural.”

He said a buy-up program was the only meaningful solution because “anything short of this will not work. Legislating the land does not legislate the man and without eager, dedicated farmers there is no farming.”

Fast forward over four decades later and his cousin, Peter Guichon, one of Delta’s best known farmers today, explains farmers weren’t upset at losing the ability to sell their land for other purposes but mostly losing land value. However, he says there’s no doubt the farm reserve saved the region’s valuable farmland from being paved over with strip malls and single-family housing.

“Back then there was almost no talk or worry about food production and growing local didn’t even enter the rest of the public’s mind. The farmers were concerned it would devalue their land but I’m not sure that turned out to be true,” Guichon says.

“If that bill didn’t come in, there would be no more farmland in Ladner or Tsawwassen and most of the Lower Mainland, so I think if you ask most of those same farmers now, their opinion would be a total reversal of what the mindset was back then.

“It was a shock to them at the time but I can say it was a way worse shock, way worse, four years before that when the government expropriated from them 4,000 acres (for future port-related industrial development) and that was a way harder pill to swallow for the local farmers than the ALR ever was.”

Delta South MLA and former city councillor Ian Paton, an East Ladner hay farmer whose father, Ian Paton Sr., was an ALC chair and champion for the reserve, agrees places like Delta and Richmond would look very different today had the ALR not been around.

The City of Delta, unlike Richmond, has also been pro-active in keeping farming viable through such policies as not allowing large farms to be subdivided and limiting the size of farm houses, he notes.

“My dad used to always say that the biggest issue with the ALR is keeping big farms. A rich doctor or lawyer with a two- or three-acre hobby farm, it’s not really feasible or practical to farm that. That was a problem back in the ’70s with way too much subdivision of farms into little farms and the owners may not have been farmers. Maybe they had a daughter who had a horse or kids wanted to ride their motorbikes and a lot of those little farms never got farmed. There was a lot of that in Surrey and Langley and places like that but not so much in Delta,” explains Paton.

“Personally, the ALR was a good thing because in Delta we have such wonderful Class 1 and Class 2 soils and it’s very important we kept warehouses off them. Let’s look at the TFN (Tsawwassen First Nation), that’s a very poor example of a treaty signed and the biggest loss of farmland but nobody dares says anything about it. There’s hundreds of acres of farmland now covered up with sand and gravel and they’re building houses on it or warehouses. In Delta, probably the biggest use of land coming out of the ALR was for government-related things like railway lines, Highway 99 and the South Fraser Perimeter Road.”

According to the province, about 10,181 hectares (25,157 acres) of Delta’s total land area of 36,433 hectares (90,027 acres) is in the ALR. That works out to about 28 per cent.

However, not all of Delta’s ALR is being farmed because only around 59 per cent have “agriculture and hobby” listed as the primary land use activity.

Not everyone is a fan of the ALR, including the Fraser Institute, which states British Columbians have grappled with land use restrictions that rank among Canada’s most severe since the reserve was established.

“The rationale for denying citizens the full use of 4.7 million hectares of property has shifted over time, from rescuing the ‘family farm’ to preserving ‘green space’ and, most recently, protecting the ‘local’ food supply. The costs of this social engineering, which include soaring housing prices resulting from a scarcity of land for development and the incalculable loss of property owners’ economic freedom, are substantial,” according to a Fraser Institute report 10 years ago.

“Champions of the ALR claim that the land use controls are necessary to ensure a ‘local’ food supply. But B.C. consumers have shown an undeniable preference for greater choice. The vast majority of B.C. consumers buy great quantities of imports and base their purchase decisions on a range of legitimate factors, including price, variety and convenience, rather than product origin alone. Indeed, after three decades of the ALR regime, B.C. farmers produce just one-third of the food needed in the province to meet the standards of a ‘healthy’ diet (British Columbia, Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, 2006).”

The report also notes that land scarcity has rendered the Vancouver housing “severely unaffordable” and that the reserve has not halted the decline in the number of B.C. farms or the loss of family farms.

Delta’s agricultural plan, which new Mayor George Harvie during last fall’s civic election campaign promised would undergo an update, points out some of the challenges facing farming here today, including loss of processing plants, infrastructure intrusions, market competition and wildlife, among other factors.

“Agriculture competes for farmland with various non-farm uses looking for acreage, pastoral setting, profit on speculation and spaces to carry on non-farming activities. ALR farmland is highly attractive for rural residential purposes and there is a market for storage of trucks, equipment and recreational vehicles on farmland. Such uses subvert the intention of the ALR and reduce the area available for farming,” the agricultural plan warns.

Concern has also been raised more recently that escalating land prices due to speculation will prevent younger generations from entering farming.

The provincial government recently appointed a special advisory committee to look at ways at strengthening and revitalizing the ALR, and make recommendations for new legislation.

In the committee’s interim report last year, one of the recommendations to curb speculators looking for exclusions from the reserve, and for subdivisions or non-farm uses, is to create a “defensible and rationalized ALR boundary with a long-term land use planning lens.” That would be achieved through a new joint local government-ALC land use planning process.

The report also notes that directing exclusions through such a process will help eliminate speculative purchasing and holding of ALR land as well as help maintain a contiguous reserve to avoid infiltration of non-agricultural uses, thus stopping “death by a thousand cuts.”

The committee also submitted a “What We Heard” report on the feedback it received during its consultations, which notes, “Overall, findings from stakeholder consultations and public engagement supported a much stronger approach to protecting and preserving the ALR for agricultural purposes. There were concerns expressed that ongoing use and removal of ALR lands for development and non-agricultural purposes, including housing, have challenged the resilience of both the ALR and ALC.”